I want to talk about Parul Sehgal. I’ve read her work for many years now, but recently, it was this interview with Paul Holdengraber that got me thinking deeply about her work. In fact, I lie. For a few days, I’ve been trying to trace a memory of reading the word “purchase” not as a verb, as it is commonly used, but as a noun. I couldn’t remember where I had read it, but it kept niggling at me, rushing back and forth like a wave in my mind. I knew I had read it in a beautiful sentence a while ago; I knew the word had been used in the context of ideas, and not in its economic or physical meanings. Then, all of a sudden, it came rushing back. In a review of James Wood’s book Serious Noticing, Sehgal mentions a Chekov line quoted by Wood in the book (“the poplar, the lilac and the roses”) along with Wood’s pungent memories of a childhood in England. She then finishes the review:

Little in “sanitized” adult American life, where Wood is productive and content, seems to have the same kind of purchase as those bygone places and people, that bygone music. He does not tell us — he does not need to — where those vivifying details can still be found (“the poplar, the lilac and the roses”).

I have gone back to this review so many times since it was published three years ago. I have not read Wood’s book yet, although I intend to. The last few paragraphs have stuck to my mind and phrases from it often rise inside me.

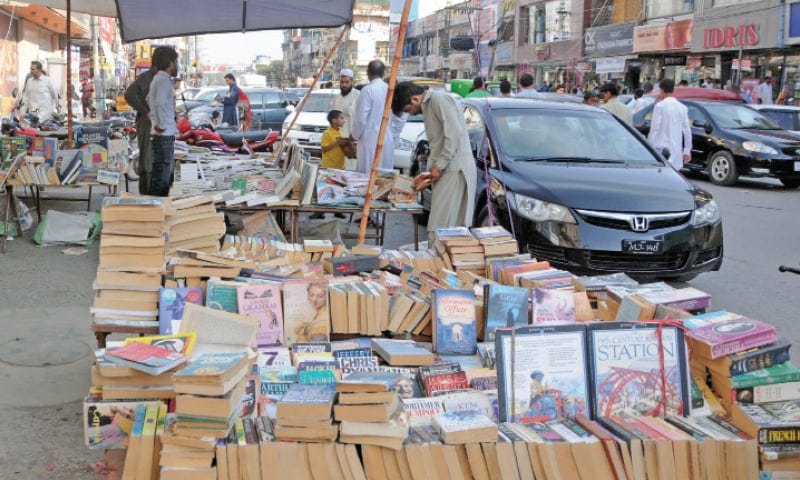

So, anyway, I re-read the review again, and then happened upon the interview I mentioned above. It’s a delightful conversation, full of wisdom and generosity. I recommend it. At one point, Sehgal talks about sneaking books from her mother’s library, a place full of “fantastic, corrupting books” she and her sister were forbidden from reading. And so of course they did. She says she came to reading in a way that was not systematic, based mostly on what book she could access and steal from the library, in a way that was governed by appetite. This resonated with me, and I imagine would resonate with anyone who didn’t have a curated reading experience as a child and adolescent. Books were hard to get throughout my childhood, and so I remember begging a neighbor who seemed to have unlimited access to them, and I remember her getting irritated and then finally throwing down random books from her terrace into my welcoming arms below. The library at the school my mother taught at had two bookcases stocked with young adult fiction. There were the old book banks in Sadar, and every few months we collected any old book in the house that could be sold off in exchange for other old ones. This is perhaps why I have no fetish for the book as an object, why my bookcase is still quite bare. Books were never a possession. They did not belong to you, and if they did, they were likely to be threadbare paperbacks thumbed through others before. They were something to be read, the knowledge and language inside them desperately ingested to staunch a certain hunger, and then returned.

The thing is, a lot of the books weren’t good. There was Sweet Valley, and Nancy Drew, and hundreds and hundreds of Archie Comics, American effluvium that somehow made its way over, the equivalent of donated sweatshop items that make their way back to their countries of origin every year. Yes, there were also Dickens and Austen and Bronte, and actually, a very smart friend of mine has a theory that we liked the Victorians because their novels mostly taught us how to read them. Given that we were so self-directed in our reading, i.e. when we even had the choice of direction, we gravitated towards content that was simple and legible, something that did not have a specialized language, like theory.

Sehgal appreciates her non-systematic introduction to reading, and often I do as well. Today, when I have access to two different library systems (I sent a letter to a NYC friend addressed to myself so I could pretend I’m a resident and get a NYPL card), still have access to a university library, can buy the few books that I wish to own or can’t find at these libraries, I sometimes cherish those days when books felt like contraband, an item haggled or begged over, something purloined. But at other times, I wish there had been some curation, someone looking over my shoulder and telling me what to read.

(Sunday Bazaar in Rawalpindi, photo courtesy Dawn)

Anyway, back to Sehgal. I am so entranced by her mind and language, the way she makes the short review a work of art, high literature about literature. Some of my favorite reviews from her are:

This blistering review of Salman Rushdie’s Quichotte (which led to Rushdie having a bit of a breakdown on Twitter)

This recent one on Jenny Oddell’s book Saving Time

This rave review of Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show

The funny thing is that I have never been actually read / shunned a book based off of a Parul Sehgal review, because my method of coming to books involves lots of playing telephone (I read a book that mentions another book, and on and on) or then, as I mentioned in the previous newsletter, catching up with the dead. The obituary does more to goad me than the review does. I read Sehgal for the pleasure of being inside her mind, trying to understand how it works, and specifically, how she translates those workings into clean, incise, beautiful prose that speaks, more than anything, of the pleasure of reading. She frequently inserts herself into the review. She speaks of the effect, mental or even physical, that the book had on her. In the Schulman review, she writes, “I understand but can’t quite accept that this book is about 700 pages long — not when I tore through it in a day; still now, while fact-checking this review, I can scarcely skim it without being swallowed back into the testimonies.” To someone who grew up thinking of books primarily as portals to pleasure, I delight in the voyeurism of seeing another reader, and that too a brilliant critic, enjoy herself, and be explicit about it.

xx,

Dure

I read the Parul Sehgal article on Odell because of this newsletter and OMG. My favorite bit was “It is not an unusual experience to feel that one’s time has been misused by a book, but it is novel, and particularly vexing, to feel that one’s time has been misused by a passionate denunciation of the misuse of time”. That’s gotta hurt 😳😬. Thank you for the rec.

I wish you write more frequently.