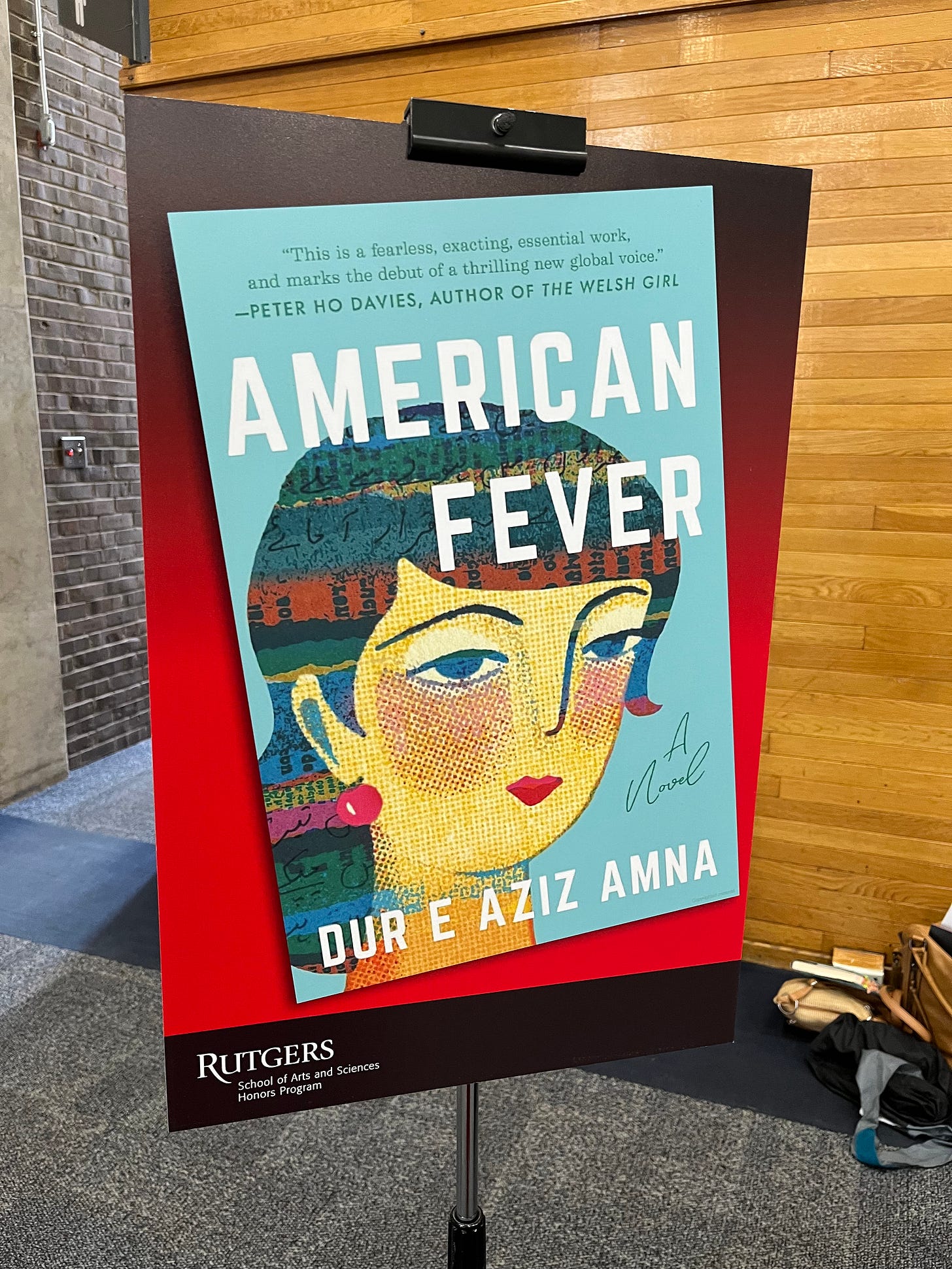

Yesterday, I spoke at Rutgers, the state university of New Jersey. I was invited to speak to incoming first-years in the Honors Program, members of the class of 2027 (!) They were brilliant and sweet and made my heart hurt a bit with their youth. Anyway, I was invited to speak about my novel American Fever, which was assigned summer reading for them. It turns out the Dean found the book at a public library and decided to assign it to 400 students; my debt to libraries continues to grow. I’m including below the transcript of the speech.

Towards the end of the Irish writer Colm Toibin’s novel, Brooklyn, there is a stunning scene that I will never forget. Eilis, the young Irish protagonist who moved to Brooklyn for work, has returned to Ireland to mourn the death of her sister. At the end of the story, she decides to leave behind the Irishman who is courting her and make her permanent home with her husband in Brooklyn. She stands on the deck of the transatlantic ship that will bring her back to America, pondering on her decision. A decision, Toibin writes, that “would come to mean less and less to the man she is leaving and would come to mean more and more to herself.”

I read this sentence at a time when I was putting the final touches on my own novel, American Fever. It had the effect that all great fiction does. It made time and space melt away. I read it again and again, weighing each part of it. Eilis was leaving home forever. This decision would disappoint the man who wished for her to stay, but over time, he would forgive her, marry someone else, move on. But for Eilis, this critical juncture, this fork in the road, would only grow in meaning over the course of her life. Every decision she made, every blessing or calamity that befell her, would be linked back to that one journey across the ocean. Of course, life is all a series of decisions but that particular one, Toibin predicts, will come back to haunt her over and over again.

I also reacted so strongly to this sentence because, as I said, I was deep in the edits on my own novel, which is also about leaving home. Eilis was a white Irish woman leaving small-town Ireland in the 1950’s. Hira, the protagonist of American Fever, is a 16-year-old teenager leaving urban Pakistan in 2010. How much can they really have in common?

A lot, it turns out. Because leaving home, while being such a specific experience of loss and gain, is at the same time a universal one. Many of you might have done it already. Perhaps in a less drastic way than Eilis or Hira, but you have left the narrow, domestic life of home to enter the larger, more public arena of college. Perhaps you are no longer living at home. Perhaps you have left hometowns around the country or state to come here. Currently, there might be a parent somewhere, woundedly looking at a tightly made bed, at a bedroom excavated of the possessions of a beloved teenager off to college. There might be a friend, maybe someone more than a friend, who is feeling the shape of your absence. And you, meanwhile, are gathered here, your heart pulled in two directions. On the one hand, the forever tug of the past that tethers you, the tug that Hira continues to feel throughout her time in America. On the other, the future that beckons, the friendly faces, the brilliant minds of those around you. On the one hand, home. On the other, the transformation that awaits.

But what if I told you that it only gets harder? What if I told you that the tug you feel, the tender place inside of you that aches for home, or a remembered, imagined, self-rendered version of it, will continue to ache, or then if it is not aching right now, one day soon it will? What if I told you that just like Eilis, your decision will mean less and less to those you left behind and more and more to you?

This, in many ways, is the central concern of American Fever. While the novel starts and ends in Pakistan, it is mostly set away from it, and yet, is it? The novel, like its protagonist, is obsessed, I’d say even haunted, by home. More specifically, it is haunted by an imagined home, the place Hira keeps returning to in her thoughts even as the long distance and quarantine prevent her from physically returning to it. Even when she does return at the end of the novel, we see that it is not the place that she had imagined, because that place no longer exists. Like the tree in the backyard of her house that has since been cut, that home is simply a phantom, a memory, but a very persistent one. It would be a cruel but perhaps fair thing to do, to take Hira by the shoulder as she sits in the backseat of her parents’ car, disgruntled by how little the place she has returned to is aligning with her memory of it, and tell her, “Darling, welcome to the rest of your life.”

But Hira is a fictional character, one that exists only within the 200-some pages that you were assigned to read this summer. Instead, I will turn to all of you and say, “Darlings, welcome to the rest of your life.” The decision you have made, to apply for college, to leave home, to come here, will reverberate for the rest of your life. I myself left Pakistan in 2011 to come to college, and I am stunned by how much of it comes back to me, unasked, at the most inopportune times of the day. I have forgotten nothing. And so, right now, that parent sitting in an empty house is feeling your absence, but over time, it is you for whom this decision will mean more and more. Everything you do will be traceable to this fork in the road. No pressure, right?

But perhaps that is too much pressure. Let us move past the nostalgia of home, past this longing for the past. Let us reorient. What the decision to leave home essentially does is that it raises the stakes of your life. I have a distinct memory of sitting at an office desk somewhere in suburban Connecticut, a few months out of college, bored and disgruntled out of my mind. It was my first job out college, a job that was giving me a good amount of money, a thousand headaches, and absolutely no fulfillment. At one point, I asked myself, “Did I really leave home and family and language behind so that I could push paper at this horrid place all day?” As luck would have it, my visa ran out soon after, and the American government refused to give an English major another visa to work at a hedge fund. Served me right, some might say. But for me, the decision to leave home at a young age has provided immense motivation throughout my time in America. Every time I have found myself in a situation that is intolerable, that is not rewarding or fulfilling, I have reminded myself that I am an immigrant. I am someone who has left behind so much. Shouldn’t that sacrifice be worth something? There are many factors that contribute to immigrant success in the US, but I wonder if a small part of it is that these are people who have burned ships. They have left their home, their culture, their language behind. In a certain way, they are ruthless. Any time they are confronted with intolerably bad situations, they ask themselves, “Really? All that for this?”

And so, in moving away from home, in coming to college, you have given up the right to a certain innocence. That cocoon of the childhood house, that comfort of prejudice or ignorance that one is allowed in one’s primary community, is not for you anymore. Now is the time for a more thoughtful self-presentation, a more deliberate curation of the self. Perhaps this runs contrary to the idea du jour, which places authenticity and honesty on a pedestal, high above everything else. But what if the authentic, unvarnished version of me is bearable to no one except my mother? For the rest of you, I must dress up, compose my thoughts before I speak, and more than anything else, think about how to meet you in the middle. With you, I aim for an interaction in which both of us feel that we have learned and grown, a courting of minds in which both parties feel respected. This is the broadening of horizons, the abandoning of innocence, that Hira also experiences. This provides the ground for a lot of the novel’s conflicts, as Hira tries to figure out how to interact with the new people and situations around her. She realizes that in America, it is not appropriate to squeeze a random child’s adorable red cheeks. She realizes that she and Amy, despite both being teenagers, have lived completely different lives. She realizes that outside of her family home, she is a person who presents a certain way, talks with a certain accent, has certain biases, and that these things are noticed by those around her. While a big part of the novel is a commentary on American mores and social norms and how they appear to a foreigner, a lot of it is Hira grappling with the questions that you all will be facing in the coming weeks. How do you present yourself in a more public setting? Who are you when the autopilot mode you have lived your childhood and adolescent years in has fallen away?

Perhaps what I am speaking of is the idea of crossing borders and the transformation that can come from it. The start of college, like moving to a different country, is a threshold that disappears once it is crossed. Just the way Hira was unable to go back to the home she remembered, college is a threshold, a transformation, that cannot be revoked. The interesting thing about American Fever being told from the perspective of a young person is that Hira is not yet privy to all that she is gaining in that one year of her life. She is acutely aware of all her losses, everything she is missing, the illness she is facing, but she cannot yet understand the worth of all that she is gaining. She is becoming more fluent in a language, trying foods she has never eaten before, meeting people unlike her in every way. She is learning that she hates volleyball, that she loves the feeling of wind on her bare legs, that she is, ultimately, a person separate from her parents and her brother. And while in Hira’s case, the process through which this transformation happens is a stark, sometimes even brutal one, these border crossings happen to all of us. You will cross a border when you meet a class fellow who is very different from you. You will cross a border when you find yourself interested in a subject you had never imagined you would be. You will cross a border if you take a course in a new language, or study abroad in a new country, or meet your college friends over a cuisine you have never tried before. In the moment, these will all feel like small, throwaway incidents. But they will be accretions, slow and gradual additions to your life that will help define who you are, what you like, what you dislike. They will show you what your strengths and weaknesses are, what your natural affinities are. They will layer on you like accumulations, making you worldlier, wiser, and smarter. So that the person who dons that black cap and gown four years from today will be a different you, a transformed you.

When I was in college, our dean made us do an exercise. In a gathering much like this one, arranged at the very beginning of our time there, everyone in our class was given an unmarked envelope with a blank note inside. The instruction was to write a letter to our future, graduating self. It could be anything—promises made, hopes for the future, and so on. Four years later, right before graduation, we were handed back the letters, our names inscribed on them in our own familiar handwriting. By the way, one thing that does not change in college is your handwriting. I regret to inform you that if you came here with bad penmanship, college cannot help you. No one can. And so we all got back those letters, and there was a rustle of paper as we tore open the envelopes, and then the room grew utterly silent. We all looked down and read the letters by the people we used to be.

And in fact, the people we still were. When I read the letter, I recognized the girl in there, recognized her so sharply and painfully that it felt like a punch in the gut. There she was, as breathless and romantic as I remembered her, as poetic as I could be on my best days. As breathless and romantic and poetic as I still am, on my best days. I don’t remember if I had achieved all that she had hoped for me, but without a doubt—I was still her. A version of her. A better or worse version, I cannot tell, but a version that was much more at home in the world.

And this leads me to my final point, which is that the purpose of crossing borders, the purpose of this transformation that college encourages, perhaps even insists on, is not to estrange you from home. That might be part of the process. Sometimes, to grow, one must assume a temporary position of dislike for one’s origins. Think of Hira at the end of the novel, finding that old world of hers so limited, so close-minded and stifling. But again, the novel spans only a year, and we leave Hira in the backseat of her parents’ car, because otherwise, I would hold her by the shoulders, this time more gently, and tell her, “Darling, this too shall pass. One day, you will be at home everywhere you go.”

And that is the most essential, perhaps the only, education that college can provide. It teaches you that while the most priceless and indispensable part of you is the one that you brought here today, the one that was honed by childhood and class and race and culture, it is only when you are separated from that, when you attempt to transcend that and allow yourself to be lost without it, that you truly come into yourself. You will pick it all up again; remember, one forgets nothing. But now is the time to get lost, the way Hira did in her first few months in Oregon. Now is the time to cross borders, to move past comfort zones, to see the world through each other’s eyes. Now is the time to abandon notions of self that were prescribed by default, by the accidents of birth and geography. If you are lucky, you will come to find out that home can be a moveable feast, to be taken along wherever you go. You will know that your true home is the earth.

Thank you.

"If you are lucky, you will come to find out that home can be a moveable feast, to be taken along wherever you go."

Brilliant. Thanks for sharing.